| Interacting through photographic portraits |

|

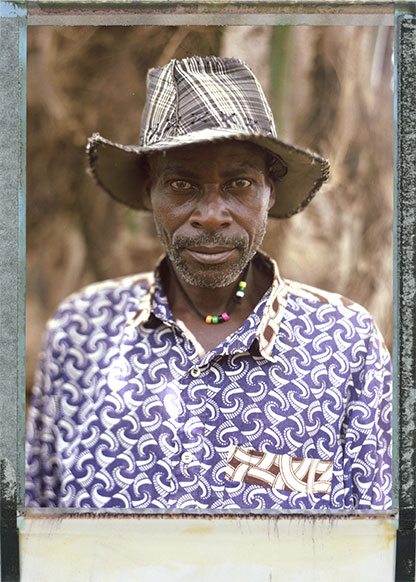

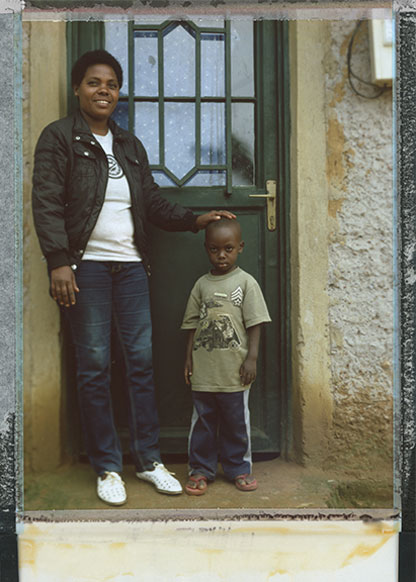

| Nowadays in Rwanda, it's very difficult to openly discuss certain matters. Referring to any type of ethnic identity can lead to jail, as can criticising the government's development policies. Rwandans are also shy about publicly expressing personal opinions, which is why the project based itself on individual portraits, taken behind closed doors. In order to break down barriers with witnesses, to make interactions more lively and more intimate, and to focus on each person and their story, regardless of their ethnic or social group, the project used a specific photographic concept. The concept of Polaroid and “unique” photo was made possible thanks to a 1937 camera (Speed Graphic + Aero Ektar lens + Fuji film), with the photo being developed immediately. Two shots were taken each time: one print was given to the person who was photographed, and the other was included in this project. Thus interactions centred around the shots taken by artist and photographer Arno Lafontaine. |

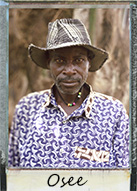

| Osée Muhebera |

| Osee Muhebera, age 49, has returned to his village after serving 14 years in jail. Back in 1994, he massacred many Tutsis and was convicted of genocide crimes. His land was expropriated and given to Tutsis returning from exile. He now farms a plot belonging to the state, but without a licence, he risks being jailed again. Osee is a confessed genocide perpetrator who has returned to his village – the crime scene. |

| Alphonsine |

| Alphonsine, 49, was accused of looting during the genocide, and her husband served a 15-year term for murder. She was acquitted by traditional “gacaca” community courts, but lives in dire poverty and struggles to feed her children and grandchildren. She is unable to pay back the money she has borrowed. Alphonsine belongs to Rwanda's class of farmers who grew poorer in the aftermath of the genocide. She is trying to find a way out of poverty, even though her husband is unemployed. |

| Jeanne |

| Jeanne, 32, genocide survivor and mother of two. Although traumatised by her family's massacre, she manages better than other survivors. She receives government subsidies, and authorities turn a blind eye to her illegal bar. Jeanne represents the younger generation of genocide survivors, who have built their lives without families around them. |